Pescetarian Life |

|

Visitor count:

FAQ's

- Humans need meat to be healthy. Why else would our digestive systems be adapted to processing animal proteins since birth?

- What about our fangs?

- People who do not consume land animals, must eat seafood to ensure they get enough protein, don't they?

- What about the paleolithic diet? Is it not the optimum diet for humans?

- What about the Inuits? Theirs is a low-carb, high-protein diet and yet, they have low rates of heart attacks and stroke.

- The Internet is full of conflicting information and studies about nutrition. Dietitians, nutritionists, diet gurus, and family physicians all have differing opinions and advice. To whom do I listen?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of eating certain foods like meats, dairy, fruits, and vegetables?

- Are humans omnivorous?

- What are the advantages of eating surf instead of turf?

- My grandfather ate what he wanted, smoked, and drank whiskey all of his life and lived to be 80. Why should I worry about the foods I eat?

- It has been suggested that humans have intestinal receptor(s) for haem (heme) iron which can only be found in animal flesh. Doesn't this mean we are biologically adapted to eating meat?

- Chimps, who are our closest relatives, sometimes consume meat. They even have the same kind of teeth as we do. Doesn't this imply meat is a natural part of the human diet as well?

- Eggs are high in cholesterol. Should I avoid them?

Q: Humans need meat to be healthy. Why else would our digestive systems be adapted to processing animal proteins since birth?

A: All mammals, whether frugivorous, herbivorous, carnivorous, or any other type(s), are adapted to digest animal protein since birth. Such an adaptation is necessary to ensure that the baby's first food, mother's milk (which contains animal protein), is properly digested.

Calves, which are herbivorous, for example, can process animal protein just as well as lion cubs, which are carnivorous. Beyond their infancy, calves and cows that are raised in factory farms regularly consume animal protein over the course of their lives. The protein comes from the carcasses of other cows, sheep, or from chicken "litter". Although cows can reach adulthood, reproduce, and live beyond their reproductive years on an omnivorous diet, they are by no means biologically adapted to be omnivorous themselves.

Most biologists agree that humans are omnivorous creatures, as are bears and raccoons, for example. This, however, does not mean we are adapted to be indiscriminate meat eaters (see FAQ # 9). Their consensus is based on their observation of human behavior (meat consumption) and the fact that humans can process animal protein from the diet. Following this line of thinking, however, cows should be classified as omnivorous as well.

So, where does this leave us? Enter bio-chemistry, organic, molecular, and evolutionary biology. These fields can open a window, for all who are interested in taking a peek, into human physiology and its interactions with the environment, which include the foods we eat. They shed light on why some of the foods we eat damage the human body in the long run, while others make us healthier and more resistant to disease.

Over the course of human history, we have strayed from our optimum diet, to such an extent, that we have become the only animal on the planet who has to concern itself with counting calories and keeping track of the nutrients in our food. We worry about lack of vitamins and fiber in the diet, so, we buy "natural" supplements. We consume dairy well into our adulthoods, something no other animal is known to do of its own volition, because we mistakingly believe it is necessary for bone health. We base our decisions on the (often erroneous) practices of the societies in which we live, as well as those of our ancestors' who only had to live long enough to reproduce and give their young a head start. We are not much different in this respect than the animals we raise for food, who live and reproduce while being fed unnatural diets, ignorant of the long term effects of our practices.

Back to top

A: What about gorilla fangs?

Impressive as its teeth may be, the mountain (as well as lowland) gorilla is a vegetarian and insectivorous animal. What we refer to as human "fangs" are pitiful representations of their kind when compared to those of other animals (i.e. bears, raccoons). There is no reason to believe their presence is suggestive of our optimum diet. Teeth are not a defining factor in this case.

Back to top

A: Seafood consumption is only a gustatory preference. It is not necessary for meeting our daily protein needs.

From the World Health Organization:

http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/5_population_nutrient/en/index.html

This translates into roughly 40 grams of protein for every 1,500 calories consumed (Fitday.com). Eating a breakfast consisting of two eggs (14 grams of protein), two slices of toast (8 grams of protein), 8 oz. of hash browns (9 grams of protein), and one glass of orange juice (3 grams of protein) results in a protein intake of 36 grams. A mid-morning snack of peanuts, or a candy bar, provides the remaining 4 grams and the daily protein needs have been met before having had the first bite of lunch. Back to top

A: The paleolithic diet was one of necessity during a time when environmental and social factors forced our ancestors to adjust as well as they could, or risk extinction. Under similar circumstances, otherwise herbivorous or frugivorous animals have been documented to consume meat. Deer and sheep, for instance, will eat bird chicks when their food sources are depleted or they need extra minerals in their diets. Does this mean sheep and deer should continue doing so once their food supply returns to normal? Are sheep to be re-classified as omnivorous? Are chicks necessary for sheep health?

Once our ancestors started scavanging for meat and hunting, they had no reason to stop. Meat, like many other potentially dangerous agents, does not show its detrimental effects right away. It takes many years, often decades, to develop degenerative diseases such as cancer, heart disease, or osteoporosis. Not seeing any immediate (harmful) effects, our ancestors continued their newly found method of supplementing their diets, and turned it into a permanent aspect of human culture. The same can be said about the discovery of tobacco, alcohol, refined foods, and recreational drugs. Does this mean we have physiological adaptations to consume these substances? Not exactly. It just means we are culturally predisposed to doing so. We're creatures of habit who learn from our parents and our social circles, then play our parts in passing on our learned knowledge, most of the time without questioning the validity of our beliefs.

References:

A:

Inuits have very little European or other ethnic admixture among their populations. In fact, "the frequencies of some typical European genetic markers, such as factor V Leiden, HFE Y282, and MTHFR 677T, are either absent or very low among the Inuit (Hegele et al. 1997a,b)." As has been proven in a wide range of instances, small genetic differences can have significant impact on how animals, including humans, react to environmental factors and pressures.

The HFE gene, mentioned above, helps regulate the amount of iron absorbed from food. In non-Inuit populations, two mutations of the gene, which allow for excessive absorption of iron, are present. Persons who inherit one of these mutations from both parents (specifically, the C282Y mutation), have a significant risk of developing hemochromatosis from absorbing too much iron from the foods they eat. Persons who inherit the mutation from only one parent are carriers of the disease. They are unlikely to develop hemochromatosis, however, they have elevated amounts of iron in their bodies. The human body has no way to remove the extra iron, so, it stores it in body tissues, especially the liver, heart and pancreas. Extra iron can damage organs and cause them to malfunction or fail.

One in eight people are carriers and an additional five in one thousand have the disorder. 13% may not sound like a lot of people, however, when we apply this percentage to large populations, as is the case in the United States or Europe, the percentage reflects tens of millions of people.

MTHFR gene mutations are a different story. About 44% of the population carry the normal version, while the rest are either heterozygous for the mutation (have one variant gene) or homozygous for the mutation (have two variant genes). MHTFR is involved in homocysteine level regulation. Mutations result in elevated homocysteine levels, thus, raising the risk for heart attack, stroke, and/or arteriosclerosis.

The mutations described above are virtually non-existent in Inuit populations, and, as such, they play an important role in lower rates of heart disease and cancer, both of which are impacted by iron regulation. These mutations are only two of several other ways in which Inuit populations, as a group, differ from the general population on a physiological and genetic level.

From a study designed to investigate potential ill effects of dietary contaminants (such as PCB's) on the Inuit population:

References

Back to top

A: First, learn about, and understand, what the "experts'" credentials actually mean.

Second, when deciding whether the results of a study are worthy of life-changing undertakings on your part, take a little time to back-trace the funding for the study in question. Try to refrain from fully accepting the results until you have done this. Many products receive air time and praise in the wake of studies funded by manufacutrers or other parties related to earning profits from the sale of said product. This is not to say the studies or their results are not trustworthy or inaccurate. It does, however, require a more critical examination of other existing data related to the product in question. For instance, the dairy industry often conducts research, the results of which are unfavorable to their products. The industry rarely, if ever, reveals such results to the media, and thus, you, the consumer. So, before jumping on the "got milk" band wagon, it is wise to look at more than just the data presented by media outlets that are financially dependent upon their advertisers, or by professionals who too often rely on the media and/or industry funded research for information in this regard.

Doing all of this can be difficult, in part, because most people latch on to information which supports their biased points of view as soon as they encounter it, and because most don't have the time to do their own research.

"Experts" come in a variety of flavors. The following information may help shed some light on common misconceptions regarding the most commonly encountered nutrition authority figures.

Dietitians

Dietitians, unlike most nutritionists, are registered and certified. They must successfully complete a Bachelors Degree through an American Dietetic Association (ADA) accredited program. Some dietitians also hold Masters Degrees. Coursework generally includes: economics, statistics, biochemistry, physiology, nutrition for various life stages, home economics, food management, and business administration. All of this amounts to expert knowledge of the nutritional value of foods, human nutritional needs, dietary deficiencies and how to address them.

What appears to be lacking is comprehensive knowledge of the long term effects some sources of nutrients have on the human body. One very common example of this problem is reflected in what we are told regarding osteoporosis. Osteoporosis refers to the thinning of human bones as we age. Wrist, hip, and spinal bones are most frequently affected. As a result, these bones often collapse leading to diminishing stature and a stooping forward of the body. Afflicted persons appear to have a hump and experience great difficulty in trying to stand up straight. Bones, brittle and porous, break easily.

Thanks to "Got milk?" commercials and other advertisements of this kind, most people are under the impression that osteoporosis is a condition resulting from not enough calcium in the diet, and as such, can be combatted by drinking milk and/or consuming cheese and other dairy products. This is incorrect. Osteoporosis is a condition resulting from the body losing too much calcium from the bones. This is a very important point, one that seems to be lost on the dairy and supplement industries and the dietitians they have on staff. The Harvard Nurses Health study, which observed over 75,000 women for 12 years, concluded that increased milk consumption does not confer a protective effect against hip or other fractures. In fact the report suggests that increasing calcium intake from dairy foods is associated with a higher risk of bone fractures. Hormones and dietary choices are among the primary culprits behind osteoporosis, not the lack, or insufficient amounts, of dairy in the diet (at least not for persons living in developed nations where food is easily available).

The hormonal changes that occur as women get older are a normal part of the aging process. Exacerbating the negative effects of these changes, through poor dietary and lifestyle choices, appears to be a common habit among members of western societies. Lack of awareness is to blame.

For another example of misleading information, take a look at the difference between heme and non-heme iron.

One possible reason most dietitians recommend dairy as the magic bullet may be the source of funding for many dietitian continuing education credit courses (CECs) and learning materials, as well as for a considerable number of American Dietetic Association (ADA) programs. The ADA accredits the undergraduate and graduate degrees necessary for dietician certification. To shed some light on what this means for you, the consumer/patient, here are some excerpts from the Center for Science in the Public Interest report on industry funding, downloadable in its entirety at cspinet.org. Be sure to download the "Introduction" file as well as the full report. Both files are in PDF format. If you do not have Acrobat Reader installed on your computer, you may download the software from Adobe.

Nutritionists and Diet Gurus

Unlike dietitians, nutritionists and diet gurus are not required to have special education or certifications to practice nutrition counseling, or profess and publish their books. It is thus easy to see why they often contradict each other and fail to agree on anything.

That being said, a minority of nutritionists are, in fact, formally educated in human nutrition. An accredited university degree at the Masters or Doctorate level sets such nutritionists apart from the vast majority who have no formal education in this field, or who hold other, often times unaccredited, or worse, completely unrelated university degrees. It is up to you, the consumer, however, to ask for information regarding the nutritionist's education/credentials prior to engaging in a client/therapist relationship.

There is only one trustworthy nutritionist certification organization in North America at this time: the Certification Board for Nutritional Specialists. Unless the nutritionist holds an advanced university degree in Human Nutrition from a regionally accredited institution and/or s/he holds the Certified Nutrition Specialist (CNS) title, consumer beware. Always ask to see the practitioner's grad school diploma or CNS certification before deciding whether to move forward and, thus, become financially responsible for receiving his/her services.

From Quackwatch.com:

A Certified Clinical Nutritionist (CCN) credential is offered by the Clinical Nutrition Certification Board (CNCB), an organization founded in 1991 to provide credentialing to nutrition professionals who might not be eligible to become registered dietitians or to be certified by the American Board of Nutrition. Although some members are qualified and practice appropriately, both CNCB and its sponsoring organization (the International and American Associations of Clinical Nutrition) include promoters of highly dubious practices among their leaders.

American Health Science University offers a Certified Nutritionist (CN) credential to students who complete its six-course distance learning program and take an examination. Although accredited, it is closely aligned with the health-food industry and should not be regarded as trustworthy. Its president, James R. Johnston, does not appear to have a accredited doctoral degree.

The American Association of Nutritional Consultants issues a Certified Nutritional Consultant (CNC) credential to persons who take an open-book test. The CNC credential should be regarded as bogus.

The Society of Certified Nutritionists (SCN), established in 1985, includes Certified Clinical Nutritionists (CCN), Certified Nutritionists (CN), and Certified Nutrition Consultants (CNC) among its members. SCN membership should be regarded as a sign of poor judgment.

Beware of Unqualified Individuals

Because the titles "nutritionist" and "nutrition consultant" are unregulated in most states, they have been adopted by many individuals who lack recognized credentials and are unqualified. In addition, a small percentage of licensed practitioners are engaged in unscientific nutrition practices. The best way to avoid bad nutrition advice is to identify and avoid those who give it. I recommend steering clear of:

Physicians are generally no more informed about nutrition than the bulk of the general public. The difference, however, is that unlike the general public, most physicians will not admit their lack of knowledge. When asked for advice regarding nutrition, far too often they do not hesitate to give it. This is unfortunate indeed, since most people trust their family physicians with all aspects of their health, not just with damage control once sickness has already settled in.

Recent studies and surveys revealed that the vast majority of medical schools offer only basic nutrition courses, most as electives, to their students. This is not surprising, since a physician's main purpose is to fix existing health problems, rather than to engage in preventive medicine. They are experts in the former, but inadequately informed/educated in the latter. From PubMed:

Perhaps the worst part of all this is that in spite of their overwhelming lack of training, over two-thirds of physicians provide dietary counseling to their patients, who, trustingly follow the advice they receive. The bottom line, in this writer's opinion, is this: if you're sick, see a doctor; if you want information on designing a healthy diet, see a dietitian or a nutrition counselor with proper credentials.

References

A:

References

Back to top

A: Depends on what one means by "omnivorous". A better question would be "are humans adapted for meat consumption?"

An animal who is physiologically adapted for, and consumes, both plant and non-plant based foods is defined as omnivorous. However, an omnivorous animal is not, by definition, a meat eater. Meat eating omnivores and non-meat eating omnivores have similar biological adaptations and gut bacteria to help them process foods that are not of plant origin. Labeling humans as omnivorous does not say anything about whether we are physiologically adapted to dine on steaks. It merely points out that we carry physiological adaptations for processing animal based foods. Eggs and invertebrates are all animal based foods. They are not, however, "meat" as it is commonly defined (i.e. the flesh of fish, birds, or mammals).

Unlike the labels "carnivorous" and "herbivorous", the omnivorous label covers a wide range of animals which may be primarily vegetarian or primarily carnivorous. For instance, Bonobos, who are primarily frugivorous and whose diets consist of 2% to 3% meat and 97% to 98% plant based foods, are labeled omnivorous, as are lowland gorillas whose diets consist of plants, fruits and insects, and bears whose diets range from primarily carnivorous to exclusively plant based (i.e. the Panda).

Humans are physiologically best suited for a primarily frugivorous diet, complemented by eggs and invertebrates. All of these provide animal derived nutrients, such as B12, without increasing the degenerative disease(s) risk associated with meat and dairy consumption. As such, we may be classified as omnivorous, but not necessarily as meat eaters.

An omnivorous animal adapted for meat consumption, such as the bear, does not:

References

Back to top

A:

Any diet that limits meat consumption is a step in the right direction toward good health. Pescetarians generally consume a light to moderate amount of seafood, while the bulk of the diet is vegetarian in nature, characterized by fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, grains, eggs, and heart-healthy oils. Such fare provides a sizable intake of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals, and a low intake of saturated fat, animal protein, and heme iron, thus, protecting the body and, on a larger scale, several areas of the environment.

Back to top

A: There are some deceiving factors in play in this line of thinking.

The first has to do with our perceptions of health. Most of the illnesses or conditions that afflict the aging population are things we think of as being a normal part of aging: arthritis, impotence, varicose veins, brittle bones, digestive problems, tooth decay, prostate problems, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, not to mention a variety of cancers and heart disease. The list goes on. While it is true that some ailments can be blamed, in part, on genetic make-up and/or old age, most can be ameliorated, and some can be avoided altogether, because, contrary to popular belief, they are not an inevitable part of the aging process.

We are accustomed to seeing these "normal" ailments in the older population and thus, we assume that our acquaintances, or some of our relatives, who live long lives are healthy. After all, many are not laid up in hospital beds, or worse, living in long term care facilities. We equate longevity with quality, but they are not the same. It is one thing to still go hiking, for example, at 80 years of age, and quite another to spend one's golden years avoiding strenuous activities in an effort to manage a host of degenerative/debilitating diseases.

Longevity as a result of "good genes" and the ability to repair one's cellular damage at higher rates than the general population, are partly the work of polymerase 1, an enzyme which repairs DNA damage very quickly and efficiently. Approximately 6% to 10% of the global human population is blessed with a mutation, affecting the otherwise decreased levels of this enzyme in the aging population, and/or overactive endothelial progenitor cells (which repair damage to blood vessels). Using the 10% figure, this amounts to a whopping 657 million people, meaning every person reading this page has met, heard of, or is related to, someone who seems to stay healthy regardless of lifestyle or dietary habits. One example of people carrying high levels of this enzyme are the heavy drinkers and smokers who live well into their 90's and suffer few (if any) visible, detrimental consequences.

While this may be a wonderful thing for 6% to 10% of the population, it is by no means the same for the rest of us 5.9 billion people who have to make certain we don't purposely damage our bodies by eating poorly, smoking, drinking heavily, or using recreational drugs.

References

A: No, for two reasons. First, some vegetarian animals, such as the guinea pig, have intestinal heme iron receptors (Latunde-Dada, 2006). Second, humans are adapted for invertebrate consumption (i.e. omnivorous adaptations) so, it should come as no surprise, that we may have heme iron receptors to handle the job. (Many invertebrates contain heme iron.)

References

Q: Chimps, our closest relatives, sometimes consume meat. They even have the same kind of teeth as we do. Doesn't this imply meat is a natural part of the human diet as well?

A: Humans and chimps may be related to a certain degree, but we are not the same species, anymore than eagles are the same species as Canadian geese. The first is a carnivory predator, while the latter is a grass grazing vegetarian (see Grizzlies and Pandas as another example).

The genetic similarities between chimps and humans, in some instances, are less important than the differences. Consider this:

"The greatest differences between humans and chimpanzees occur in the canine teeth. Small peg-like human canines do not project from the tooth row. In contrast, chimpanzee canines are much larger, robust, and project far above their tooth row. Diastemas, gaps in the tooth row of the maxilla allow projecting mandibular canines to pass the opposing canine and incisor during occlusion. The maxillary canine passes the buccal side of its opposing pm3, allowing the lingual surface of the canine to make contact with a blade-like sectorial surface on the premolar. Humans lack the large diastema and the human pm3 is non-sectorial. Human anterior teeth (canines and incisors) are greatly reduced in size and human incisors are positioned close to a transverse plane that passes through the canine teeth. Chimpanzee incisors are positioned well forward of this plane. Consequently the parabolic or elliptical human dental arcade contrasts sharply with the U-shaped arcade of chimpanzees. Human molars tend to be rounder and more compact than chimpanzee molars. Occlusal molar surfaces of human teeth are relatively flat, and quickly become even flatter with attrition (Department of Anthropology, University of Texas)."

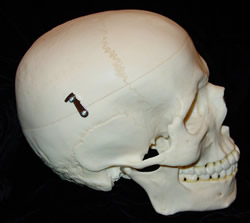

Compare the canine teeth of a chimp (whose teeth are very similar to, and almost as impressive as, those of the vegetarian gorilla) with those of a human:

Although genetically similar, chimps are only 29% identical to humans when the number of proteins we share are measured. This difference is significant and can account for a large variety of traits the two species do not share (Chimpanzee Sequencing 2005).

Whatever similarities exist among chimps and humans, we are, none the less, different species. Mimicking the habits of another species makes no sense, particularly in light of some rather undesirable aspects of chimpanzee behavior, such as infanticide and consumption of one's own faeces.

References

Eggs are fairly low in saturated fat (on average, about 1g to 1.5g per egg) and they do not contain significant amounts of heme iron or other potentially detrimental agents. As such, they are safe to eat in moderation. In addition, eggs are a natural source of B12, vitamin D, riboflavin, and folate. While they are not high in saturated fat, however, they are high in animal protein, and, as such, contribute to the formation of kidney stones over time if consumed in generous quantities. Two eggs per day, three to four times per week, is the maximum limit one should set for him/herself.

References

Q: What about our fangs?

Q: People who do not consume land animals, must eat seafood to ensure they get enough protein, don't they?Carbohydrates should provide the bulk of energy requirements - between 55 and 75 percent of daily intake and free sugars should remain beneath 10 percent. Protein should make up a further 10-15 percent of calorie intake and salt should be restricted to less than 5 grams a day. Intake of fruit and vegetables should be plumped up to reach at least 400 grams a day.

Q: What about the paleolithic diet? Is it not the optimum diet for humans?

Back to top

Q: What about the Inuits? Theirs is a low-carb, high-protein diet and yet, they have low rates of heart attacks and stroke.Dietary MeHg showed no association with the examined oxidative biomarkers, whereas PCB level was a predictor of the plasma concentration of OxLDL, although this concentration remained very low. The level of GPx activity in Inuit was higher than levels previously reported to be protective in whites. Homocysteine was negatively predicted by Se, suggesting a possible beneficial effect of Se. Moreover, n-3 PUFAs were highly correlated with dietary contaminants, but had no relationships with oxidative biomarkers. This study suggests that, in adult Inuit, contaminated traditional diet seems to have no direct oxidative effects on molecules involved in oxidative stress.

Many other differences exist, such as the unusually small quantities of alcohol dehydrogenase present in the livers of Inuit adults, the effect of which is evident in that a grown Inuit man can become intoxicated from as little as half a pint of beer.

Q: The Internet is full of conflicting information and studies about nutrition. Dietitians, nutritionists, diet gurus, and family physicians all have differing opinions and advice. To whom do I listen? What am I to make of the overwhelmning health/diet information available in the media and on the Internet?[...] the 70,000-member American

Dietetic Association focuses primarily on increasing the credibility and income

of dietitians, many of whom work directly for, or serve as consultants to, food

companies. That immediately raises conflict-of-interest issues, because what is

good for the public may not be good for the ADA's book balance and many

companies. The food industry sees the ADA as a vehicle for reaching the hearts

and minds of dietitians and the general public. Thus, many major food

companies - from Mars to Gerber - contribute to the ADA, advertise in its

journal, and exhibit at its annual meeting. They also sponsor "fact sheets." The

National Soft Drink Association sponsors the fact sheet on soft drinks. The

biotechnology industry sponsors a fact sheet on agricultural biotechnology.

McDonald's sponsors the fact sheet on "Nutrition on the Go." Ajinomoto, the

maker of MSG, sponsors the fact sheet on "Food Allergies and Intolerances."

The fact sheets typically are written by corporate PR firms and are lightly veiled

defenses of the sponsors' products or practices. At least, though, the fact sheets

do disclose who funded them.

Questionable Credentials

Physicians

This article summarizes the findings of a study initiative under-taken by the U.S. Public Health Service to examine its own role in fostering a more effective education of U.S. physicians in nutrition. The study was completed in response to a congressional request that the federal government examine the need for a more productive government role in this important area. The literature, dating back to the turn of the century, is relatively uniform in its conclusions that U.S. physicians are woefully under-trained in nutrition. The training inadequacy might be dismissed, indeed, has been dismissed by many programs, yet the role of nutrition in promoting health becomes clearer with each passing year. We ask: Will either the government or the medical education community begin to equip our physicians with the knowledge needed to bring nutrition into play as an active therapeutic approach to complement other therapies?

Our physicians' lack of nutrition knowledge is striking, as can be seen in the results of this study on physician understanding of the effect of diet on blood lipids and lipoproteins (from PubMed):Response rate: 16% (n = 639). Half of the physicians did not know that canola oil and 26% did not know olive oil were good sources of monounsaturated fat. Approximately three-quarters (70% of cardiologists vs. 77% of internists; p < 0.01) did not know a low-fat diet would decrease HDL-c and almost half (45%) thought that a low-fat diet would not change HDL-c.

Back to top

Q: What are the advantages and disadvantages of eating certain foods like meats, dairy, fruits, and vegetables?

Food

Pros

Cons

Refined Foods

(including sugars and flours)

Meat

(from mammals only)

Fowl Meat

Fish Meat

Dairy Products

Eggs

Fruits and Vegetables

Nuts

Grains and Seeds

Legumes

Mushrooms

Insects

Q: Are humans omnivorous?

Perhaps most telling, humans get healthier when they significantly lower, or completely stop, their consumption of meat and dairy.

Q: What are the advantages of eating surf instead of turf?

Q: My grandfather ate what he wanted, smoked, and drank whisky all of his life and lived to be 80. Why should I worry about the foods I eat?

Back to top

Q: It has been suggested that humans have intestinal receptor(s) for haem (heme) iron which can only be found in animal flesh. Doesn't this mean we are biologically adapted to eating meat?

Back to top

Back to top

Q: Eggs are high in cholesterol. Should I avoid them?

A: Yes, eggs are high in cholesterol, but contrary to popular belief, the cholesterol content of foods is unlikely to significantly increase LDL cholesterol levels in our blood. According to the Harvard School of Public Health, "The biggest influence on blood cholesterol level is the mix of fats in the diet." The main culprits in this case are saturated fats, which come from animal sources (meat, eggs, dairy) and trans fats (which are the result of hydrogenation and can be found in processed foods, particularly in cakes, cookies, crackers, pies, etc.).

Back to top